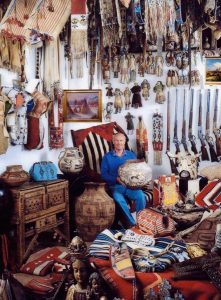

I’ve lived and worked in many cities in my time, and I’ve sat at desks in even more offices. Of all the offices in which I’ve worked, there is only one I wish I could have taken with me. The office that got away was the one I had in a sprawling adobe building filled to the gills with paintings, sculpture, pots, jewelry, artifacts and other treasures. The building sat on Paseo de Peralta in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In my twenties, I was hired by an art dealer named Forrest Fenn to set up a publishing imprint for his gallery, which was at its legendary height at the time I worked there.

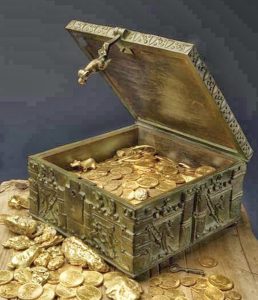

You may have heard of Forrest Fenn, who sold his gallery years ago and is now approaching ninety. At the age of eighty, Forrest morphed from a Santa Fe character into a national topic of conversation when he announced that he’d hidden a chest filled with 22 pounds of gold, jewels and relics in the Rockies somewhere between Santa Fe and the Canadian border. He published a pretty clunky, cryptic poem that he says contains the only clues needed to find the treasure, which he claims is worth upwards of $2 million. (The poem is published on many sites. Here’s one: http://fennclues.com/the-poem.html)

The Fenn treasure hunt phenomenon set the news media on fire and thousands of treasure seekers into the wilderness. Fenn uber-fan Dal Neitzel

is one of the biggest cheerleaders behind what has become such an intense obsession that four folks have died (make that five, as of 3/26/20) trying to find Fenn’s treasure chest (https://dalneitzel.com/).

There are a gazillion articles on the Fenn treasure phenomenon in publications as varied as Wired, Amtrak’s The National and even an Orthodox Jewish family-friendly publication called Mishpacha. (A comprehensive piece is on the Vox website https://www.vox.com/a/fenn-treasure-hunt-map.)

Over the years, Forrest published a series of memoirs that he says provides some hints. Word to the literary wise: The kind of writing contained in these memoirs is reflected in what Forrest says he wants as his epitaph. I quote him here: “I wish I could have lived to do the things I was attributed to.”

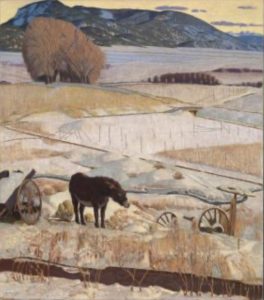

The younger Forrest Fenn who signed my paychecks back in the day assigned me the task of obtaining archives of some late members of the Taos Society of Artists. The archives, said Forrest, would serve to inform future limited edition publications on those legendary painters who had been inspired by the unique light and landscape of northern New Mexico in the early twentieth century.

My twenty-something-year-old gut told me that such documents belonged under university protection, but Forrest Fenn, who liked to brag that he never went to college, insisted that the valuable papers would be better off housed with him rather than be buried in some library vault.

My Fenn Gallery office was small and intimate. One entered my office through beautifully hewn wrought iron gates. Above were ceiling tiles covered with fragments of old Navajo saddle blankets. The built-in bookshelves were populated with art books floor to ceiling. My office had a window. It had a private bathroom.

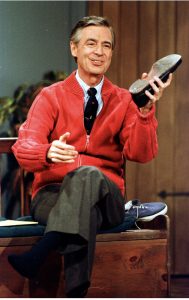

A stream of celebrities would come by to “meet Forrest” in those days, and some of them stayed in his magnificent guest house, which was a hop, skip and jump from that office of my dreams. Forrest, the perfect host to the rich and famous, would collect their autographs and boast about their visits through the years as though they were part of his list of stellar possessions. (Once I walked into his office, where he was seated holding his constant companion, his dachshund Bip, on his lap. “Mr. Rogers just signed my book,” he said, beaming.)

How, one may ask, could anyone turn her back on an office and an atmosphere like that? And yet I did, I think because I was in the midst of a crazy relationship, and the only thing I thought I could control at that time was my own sense of integrity, a sense that finally led me to telling Forrest Fenn that I didn’t want to work for him anymore.

What was the last straw that pushed me over the edge?

It wasn’t the time Forrest asked me to take a detour from the publishing/archive project and call the Albuquerque Zoo to see how he could acquire penguins to live by the massive pond that he was having built behind the gallery. Inane requests like that were part of the fun times, and there were many, many fun times.

“I don’t think penguins could survive in this climate, Forrest,” I said.

Forrest smiled, but pressed on. “I gotta believe there’s such a thing as warm weather penguins,” he declared. (Forrest never did acquire any penguins, but he eventually did procure an alligator.)

After the pond was completed, I took a lunch out to enjoy on its banks one day. But my lunch was interrupted by Forrest’s scarlet macaw named Sinbad who had his heart set on my chicken sandwich. (I’d once seen Sinbad gnawing on a chicken leg in his cage that was situated in the gallery for the bird to welcome, and sometimes screech at, gallery visitors as they entered the museum-like gallery rooms.)

Being chased by Forrest’s cannibalistic parrot didn’t push me out the office door either.

As I remember, the last straw involved my actually driving to Taos to talk face to face with an artist’s surviving relative in attempt to get papers bequeathed to Forrest’s enterprise. Though Forrest had assured me that the public would always have access to any papers he acquired, when I obtained a verbal commitment from the relative, I felt dirty.

I don’t know if Fenn ever got those particular papers, and I don’t think he ever published any books on the artist they concerned, because he was a minor one in the Taos panoply. But I knew that Fenn wanted the papers because, well, he just wanted them. Like he wanted his Indian headdresses and beaded dresses and dolls and pots and leggings and pre-Colombian artifacts and arrowheads and drums that were in the gallery’s walk-in vault. These items were on view, but not for sale.

It was clear that my boss Forrest Fenn wanted to own a history that didn’t belong to him. And through the years, it seems, he hasn’t changed. During a TV interview in 2011, a question was posed to Forrest regarding who owns the past. “Who owns the past?” Forrest said excitedly. “The guy who has the title!” (Title is an important word for Forrest. The last line of his poem reads “I give you title to the gold.”)

Some years after I left Santa Fe, Fenn actually bought property that included a large pueblo ruin so he could do his own digging without getting into trouble with the Feds. “What’ll archeologists do? They’ll just stick things in a drawer!” he said during the same 2011 interview.

To hear Forrest tell it in many interviews, the idea of the treasure chest came about after he had a visit from designer Ralph Lauren. Lauren wanted to buy a headdress out of Forrest’s collection, and Forrest told him it wasn’t for sale. “Why not?” the designer asked. “You’ve got so many, and, anyway, you can’t take it with you.”

Forrest says he thought about this comment and then asked himself why not? Why couldn’t he take it with him? He’d been diagnosed with what he’d been told was likely terminal cancer, and he made a decision that, yes, when he went, he would go holding onto a box filled with a piece of his bounty. But a problem arose with the plan, which was that he lived. But then he decided to take the treasure chest to the spot where he had planned to end things and send the world off on a chase to find it. That was in 2010. As of late 2019, folks were still posting videos on youtube (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pAloXCAdzdQ posted August, 2019 by “Mr. Luxury”) and articles online. High Country News posted a 2019 April Fool’s Day article stating that the treasure had been found (https://www.hcn.org/articles/april-fools-the-forrest-fenn-treasure-has-been-found).

UPDATE: On June 7, 2020, Forrest announced on his website (https://www.oldsantafetradingco.com/) that his treasure has been found for real ” . . . under a canopy of stars in the lush, forested vegetation of the Rocky Mountains and had not moved from the spot where I hid it more than 10 years ago.”

Around the corner from my dream office was a dream library. It was cavernous, with something like a 20 foot ceiling. There was a ladder on wheels that allowed folks to access books on the top shelf. The library was decorated with stunning pots and drums and other Indian relics.

One day, Forrest’s father came to visit. The old man, who’d been a poor school principal in a small Texas town, traveled in a small Airstream trailer that he parked in Forrest’s driveway. He was, like Forrest, an outdoorsman. He was so much an outdoorsman that when Forrest encouraged him to sleep in the celebrity guest house, he refused. He preferred the comforts of his little trailer.

I was working in the library when the old man walked in. He stood in the middle of the room and surveyed the shelves and the entire space, which was dwarfing.

“Let me ask you something, young lady,” he said to me in his Texas drawl. “Can you tell me, what’s all this for?”

I smiled at him. “I’ll be honest,” I said. “I really don’t know.”

In the autumn of 2018, I entered the doors of my old workplace, which is now the Nedra Matteucci Gallery, and I made a beeline for my old office. The wrought iron and the ceiling were there, as were the bookshelves, but they were mostly empty (it’s computer days, after all). And the feeling of the gallery itself, where many of the same artists are represented on the walls like in the old days, had a formality to it that made it hard to believe that a macaw and a dachshund and even an alligator once held court. Forrest Fenn’s uniform was always a short sleeved shirt and a pair of jeans, and jeans were de rigueur among the staff when he ruled. At Matteucci, the sales staff dressed like money. The pond is pristine, its banks populated only with nice sculptures. If you had a chicken sandwich out there, you wouldn’t be afraid of being chased by a parrot, but you’d be afraid to drop any crumbs on the manicured lawn.

In short, the place was not the same. When he sold the gallery, rapscallion Forrest Fenn, now lord of the treasure hunt, had taken something with him.